More than a Market

More than a Market

Feeding the Body and the Soul

Our lives intertwine through food—growing, foraging, selling, buying, and eating. Many of us have strong memories centered on food—holiday meals with family and friends, the smell of a favorite dish, or a lesson on how to cook a family recipe. Markets provide immigrants with the foods that connect them to memories of their homeland, traditions, and to their cultural community in a new country.

I just want to do what the people need. These peoples are like starving. You know, sometimes even me, if I like my country’s food and if I don’t get it, I feel like I’m starving. I try a lot of different foods, but I don’t get full. They’re not getting their food, but since I’m here, I’m helping them.

—Goma Khadka, co-owner, RGS Nepali Market, Burlington

My brother would talk about going in the Merola’s store down the street or Izzo’s. And just a variety of Italian cheeses. This all came from Italy, and they’d bring in big tubs of calamari around Christmas time. And he says you could blindfold him and take him in any store, and he could tell you where he was just from the smells, the cheeses, the cold cut meats.

—Michel Allen, Lebanese resident, Burlington

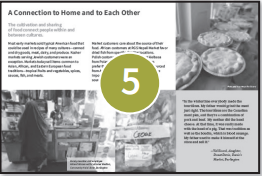

A Connection to Home and to Each Other

The cultivation and sharing of food connect people within and between cultures.

Most early markets sold typical American food that could be used in recipes of many cultures—canned and dry goods, meat, dairy, and produce. Kosher markets serving Jewish customers were an exception. Markets today sell items common to Asian, African, and Eastern European food traditions—tropical fruits and vegetables, spices, sauces, fish, and meats.

Market customers care about the source of their food. African customers at RGS Nepali Market favor dried fish from specific, familiar locations. Polish customers at Euro Market want kielbasa from Poland. Community Halal customers prefer the flavor of free-range halal meat sourced from Australia. Market owners understand the importance of this and spend hours finding a source for these products.

In the wintertime, everybody made the tourtieres. My father would grind the meat just right. The tourtieres are the Canadian meat pies, and they’re a combination of pork and beef. My mother did the head cheese. At that time, it was really made with the head of a pig. That was tradition as well as the boudin, which is blood sausage. My father used to make it himself at the store and sell it.

—Val Sicard, daughter, Donat Danis, Danis’s Market, Burlington

It may be not the same size, or it doesn’t bring a lot of money as the one in Iraq did, but it’s something that reminds [customers] of home when they come in and see some products in Arabic. It just helps them find their culture and they know that they belong somewhere, maybe even if it’s a small supermarket.

—Daughter of Ahmed Aref, manager, Nada International Market, Winooski

When I go to regular supermarket, I cannot find African food I need. So I have to go to—it can be Nepali store, African store, Somalian store, I can find the food I really need. For example, here they have halal meat, I am Muslim so I cannot eat [other meat].

—Zeynab Kouate, customer, Community Halal Store, Burlington

Searching for Food: the Market Owner

Market owners work hard to locate foods requested by their customers.

When language is a barrier, owners use photos provided by their customers to search the Internet and to show vendors at food distribution warehouses and markets in cities. Many owners make a long drive to pick up orders several times a month because of the expense and limitations of delivery to Vermont.

Earlier market owners ordered specialty items from larger cities but purchased most items from local farms, bakeries, butchers, and beverage distributors. Community members also brought back foods when visiting relatives in cities like New York, Boston, and Montreal.

We did lot of research, like we asked the customer, “Which part of Africa are you from? Congo? Are you from Burundi? Are you from Togo?” We try to collect as much information as many people as we could and the food they eat, and we try to match.

—Ratna Khadka, co-owner, RGS Nepali Market, Burlington

It’s just our traditional bread, so breadsticks we used to eat, like we walk to the school. In the city, we had a lot of bakeries in the little corners we will stop by. The store in general is a lot of memories.

—Dado Vujanovic, owner, Euro Market, South Burlington

Searching for Food: The Market Customer

Food access—its affordability and proximity to home—is a critical factor in where immigrants settle.

There must be enough markets to support the demand for traditional foods and enough customers to support the businesses.

In the first half of the twentieth century, markets were concentrated in Winooski and Burlington. Residents only had to walk a short distance to reach a market. Markets are more spread out now and may require public transportation or a car—a challenge for some new Americans.

Like many Vermonters, immigrants cultivate vegetables and fruits in backyard gardens to supplement what they purchase at stores. Some grow familiar food in plots managed by New Farms for New Americans. The informal practice of sharing surplus harvest with community members continues from the homeland to here.

Others have started small farm enterprises and import businesses to supply their communities with valued foods like eggplants and cassava products.

One of the things that made me decide to stay here in Vermont was the fact that there was Nada International Market and there was also the African market where I can come and buy food that is from home. I lived in Pennsylvania for two years, and I had to leave because there I wouldn’t find a place where to go and buy those.

—Goma Mabika, customer, Winooski

And I picked a lot of strawberries and string beans, peas. I remember filling up a bushel basket, bringing it over to the store. My father, who had the best handwriting, very flowery, he would make all the signs, “homegrown string beans.”

—Louis Mario Izzo, on his grandmother Concetta’s garden, Burlington

The Power of Cassava

It’s really a blessed plant.

—Muyisa Mutume, owner, M. Square Vermont, Winooski

Culinary traditions migrate with people and mingle in a new country. Cassava, domesticated in South America, has become a staple in Africa and Asia. Also called yuca or manioc, the shrub’s leaves are used in stews, and its roots are ground into flour or boiled, roasted, or fermented to create a carbohydrate-rich food.

Caption: Vermont-based Green Mountain Cassava supplies many local markets.

In Africa, usually, you just grab the cassava leaves, and you pound it until it’s very smooth. They’ve learned to package them in the freezer, and they sell them here. It taste like home.

—Faraja Achinda, customer, M. Square Vermont, Winooski

Caption: Frozen lamb and kwanga, a traditional cassava-based bread from the Democratic Republic of Congo,

at M. Square Vermont

[The Lebanese community] did mail order from Brooklyn, New York, and it was called the Sahadi Company. I remember the mail orders coming and having things like the snaubers, the real pine nuts. They had a thing called amardeen. It was an apricot leather, and it was rolled thin. Individual families would say what they wanted, and a big box would arrive.

—Monic Simon Farrington, Lebanese resident, Burlington

I love shopping here. Besides the family being wonderful—I know them personally—the freshness of the produce he gets from the big cities, they specialize in Asian ingredients, and really a nice diverse market. You know, it’s not just Vietnamese, it’s Japanese, it’s South Korean.

—Peter Maisel, restaurant owner and customer, Thai Phat, Burlington

Lebanese kibbeh is made with ground beef or lamb, bulgur, onions, and spices. It is traditionally eaten raw, so fresh, lean meat is important.

He’d go behind his counter into this walk-in freezer and come out carrying this humongous leg of beef. He’d flop it onto this big wooden block-cutting table and sharpen his knives. His trick was to grind it twice, and it was so tender, it was unbelievable.

—Monica Simon Farrington, Lebanese customer, George’s Market, Burlington

My father used to shop North Street. There was a lot of Jewish stores there. And I think my father was more comfortable doing business with the Jewish people because culturally they are a little closer to us and they all understood each other, and they had fun bartering back and forth. And he was friends with all of them.

—Michel Allen, Lebanese resident, Burlington

You can walk in any time, you don’t even have to buy anything, you can just chill out at the store, anything, it’s kind of like another home, to be honest. It feels like I just walk into my own house, you know what I’m saying?

—Emmanuel Braxton, customer, RGS Nepali Market