More than a Market

More than a Market

Thai Phat

An Asian Market at 100 North Street in Burlington 2007 to present

When COVID-19 shuttered all but essential businesses in Burlington in the spring of 2020, the Tran family had to make a decision about their market, Thai Phat. Should they temporarily close, as many small markets were doing in the Old North End? Their decision to remain open was a smart business decision, but it was also an expression of their commitment to their community. It was a way to thank their customers for supporting them as they built their business.

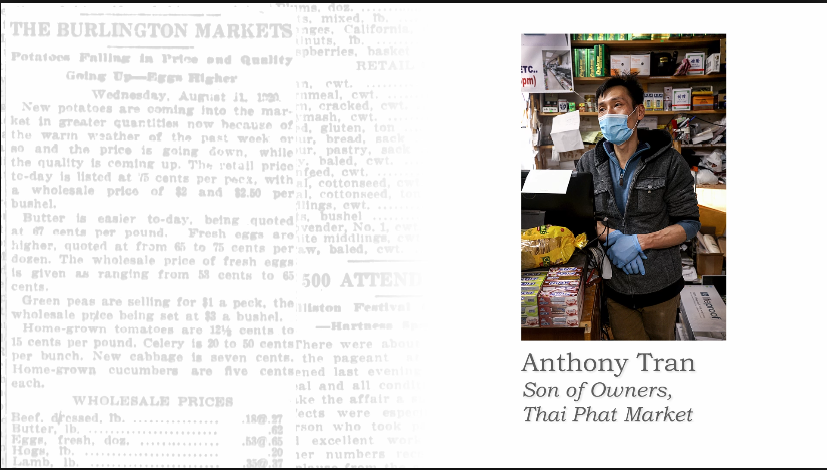

Customers and COVID

Encouraging customers to follow safety protocols was difficult at first, according to Anthony Tran, son of owners Chau Nguyen (John) and Hong Tran. Customers were upset about the requirement to wear a mask, but Anthony’s personal relationship with his customers helped. The store has signs posted in several places asking customers to wear masks and makes hand sanitizer and gloves available.

But I tell them this problem is not about yourself. About the other people and they keep going on going on. Then I have a few customer they do shopping in the store, they see it and they come and they back me up and they helping me. So right now all the customer they do it. The thing is to me, I think it’s not thinking about yourself, but thinking about all the person. If you thinking about all the person, that means you take care of yourself. —Anthony Tran, son of market owners

John and Huong Tran and their children immigrated to Vermont from Vietnam in 1993. In their village of Bien Hoa, they grew rice, fruit, and coffee, so it was a natural step to purchase Thai Phat from another Vietnamese immigrant, Andy Thai, in 2007. At that time, Anthony was employed at an auto body shop in East Hartford, Connecticut, where he had worked his way from cleaning cars to managing the entire shop. Despite the owner’s offer to give him the business, he chose to move to Burlington to help his parents in the market.

Whether chatting with customers, recommending recipes and locating ingredients, or unpacking deliveries and stocking shelves, Anthony exudes a warmth and energy that is contagious. Family members share tasks, whether washing and packaging fruits and vegetables, cutting tofu for bulk sale in buckets of water, or arranging the fresh fish for display. The market is usually open from 9:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. but stays open later if busy.

In the early years, the market served mainly Asian customers from Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and China. As interest in international cuisine has grown, so has the customer base. Restaurant owners and Asian food lovers travel to Thai Phat from all over Vermont.

Shopping for Recipes

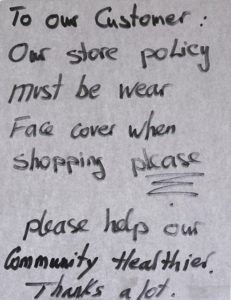

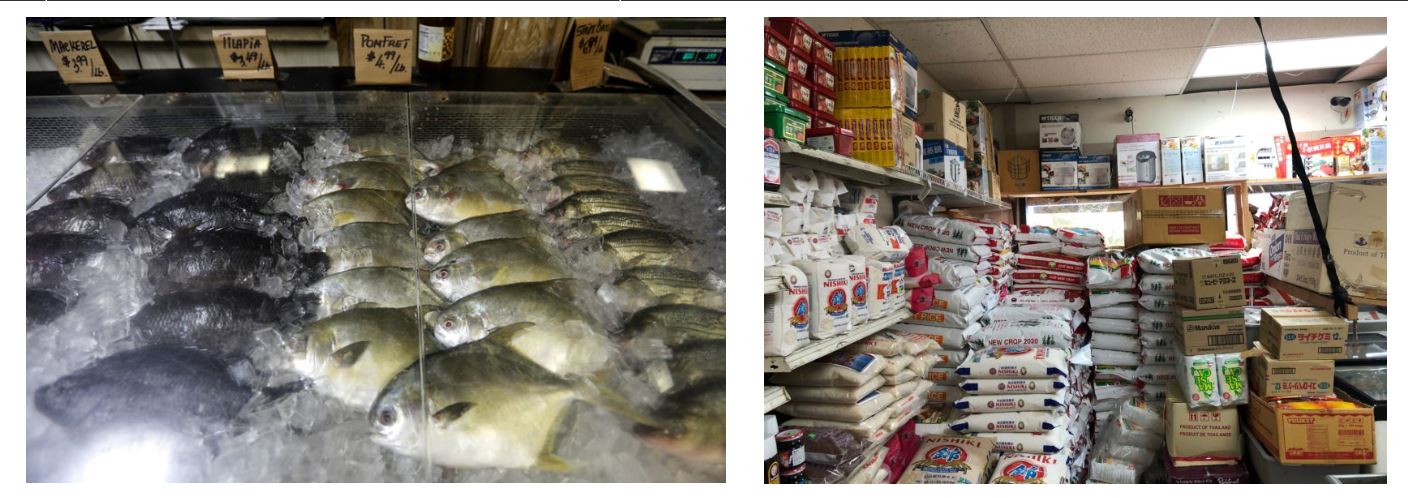

The store shelves are a kaleidoscope of sauces, spices, teas, and sweets. Greeting customers at the front are exotic fruits like durian, longan, horned melon, and pomelo. In one corner, bags of rice and noodles are stacked shoulder high; in the other, vegetables familiar and exotic are heaped together—Asian eggplant the size and color of Granny Smith apples, fresh bamboo, and an assortment of greens. In the freezer, traditional cuts of meat share space with chicken feet, pork tail, and beef omasum. The daily selection of fresh fish on ice ranges from the familiar tilapia and mackerel to skate and eel. In a cooler by the cash register are stacks of homemade banh mi, the traditional baguette sandwich of pork or beef with cilantro, pickled carrots and daikon, and soy sauce. Each Tuesday at midnight, John and Huong leave for the Chelsea Produce Market in Boston to buy items that their main supplier cannot source in New York City.

The store shelves are a kaleidoscope of sauces, spices, teas, and sweets. Greeting customers at the front are exotic fruits like durian, longan, horned melon, and pomelo. In one corner, bags of rice and noodles are stacked shoulder high; in the other, vegetables familiar and exotic are heaped together—Asian eggplant the size and color of Granny Smith apples, fresh bamboo, and an assortment of greens. In the freezer, traditional cuts of meat share space with chicken feet, pork tail, and beef omasum. The daily selection of fresh fish on ice ranges from the familiar tilapia and mackerel to skate and eel. In a cooler by the cash register are stacks of homemade banh mi, the traditional baguette sandwich of pork or beef with cilantro, pickled carrots and daikon, and soy sauce. Each Tuesday at midnight, John and Huong leave for the Chelsea Produce Market in Boston to buy items that their main supplier cannot source in New York City.

Like other immigrant families, the Trans have opened multiple businesses in close proximity to each other. Although they have been in this country for almost forty years, they continue to seek new opportunities to build a strong future for their children. In January 2020, Anthony opened Saigon Kitchen across the street and leased the adjacent storefront to his brother and sister-in-law, The, who opened Bella-Kay, a home goods and food market. Despite the challenges of feeding the public during a pandemic, Anthony has done a steady takeout business and cautiously opened the restaurant when restrictions relaxed.

Anthony and his wife, Jenny, have raised their daughters, Julie and Jessica, with the same work ethic. The girls grew up in the market, where their family tended to them and to customers at the same time. Now in high school, they stop at the restaurant after school to help through the dinner rush, then head home to do their homework until the family sits down together for dinner at 10 p.m. when Anthony finally arrives home after a fourteen-hour day.

Fiercely independent, Anthony appreciates but often eschews the offer of a helping hand. He believes in the value of lessons learned from going it alone, and he wants his daughters to develop skills that allow them to be self-sufficient. When he was in Vietnam, he used to think of America as the “golden” country, and it is everything he imagined. He has a successful business and his daughters are enrolled in high school—opportunities that would not have been possible in Vietnam. “Phat” means good fortune, and it seems that is what his family has found.

If one hundred immigrants come here, ninety-nine will be successful. Most who arrive are from the poorest countries, and they work very hard. If you start from the bottom, now you are in a place where everything is possible. —Anthony Tran