More than a Market

More than a Market

Home page intro

For almost 200 years, local markets have been a “home away from home” for many people. In cities and towns with a rich immigrant history, markets were many things—a family business, a community gathering place, and a purveyor of food. These markets were a source of emotional and physical nourishment, woven into the daily lives of residents. Here customers could socialize, catch up on local and national news and hear gossip from back home, speak in a native language, and purchase familiar foods.

Technology and transportation have dramatically changed how people shop and socialize but markets remain an essential business for many immigrant communities. The stories of markets established by immigrants and refugees, in the past and today, embody timeless American values of hard work, resourcefulness, resilience, and commitment to family and community.

In the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, neighborhood markets were everywhere in Burlington and Winooski, Vermont – on street corners, in the middle of blocks, even in living rooms. Before the automobile and refrigeration became widely available, people shopped daily within blocks of home, stopping at the butcher shop, the bakery, confectionary and fruit stands, and the variety food market.

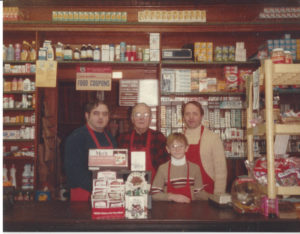

Immigrant families owned many of these markets and usually lived upstairs or nearby in order to serve customers while still involved in family life. They worked long hours, yet had the time to lend an ear or a helping hand to neighbors. While men typically were listed as the market proprietors, women were partners as clerks, bookkeepers, and even butchers. Children clerked, stocked shelves, delivered to customers, and were happy consumers of the ubiquitous penny candy and soda sold within an arm’s reach at most markets.

The arrival of chain supermarkets in the 1940s triggered a decline in small markets. Early arrivals like IGA or First National opened in the neighborhoods and thus remained part of the fabric of the community. By the 1950s many supermarkets opened in the outskirts, where large tracts of land allowed for sprawling buildings and parking lots. While small markets could not compete with the vast selection at supermarkets, they offered something else – personal service, social connection, and the specialty foods that reminded people of their heritage and culture.

From the mid-1800s to mid-1900s, French Canadian, Italian, Irish, Lebanese, Jewish, and German markets were concentrated in Burlington’s Old North End and Lakeside neighborhoods and near the mills in Winooski. Market ownership passed from one family member to another or between families in the community. Since the 1980s, immigrants from Vietnam, Bosnia, Bhutan, and Eastern and Western Africa have carried on this entrepreneurial tradition—some in the same neighborhoods, or even buildings, others in outlying suburbs where new Americans have settled. They offer staples, spices, seafood, halal meat, and grains important to the many cultures that call the Burlington area home. They are a magnet for the growing number of people who appreciate cooking and sampling global cuisine.

Today, we may find community in many places between work and home—coffee shops, library reading rooms, bookstores, community centers, religious meeting spaces—and local markets. Like community living rooms, these places offer us a place to relax, share ideas, and satisfy a universal longing for connection.

Where do you go to connect with others in your community?